The federal government ‘sees a long-term future for the oilsands.’ Here’s what you need to know

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

This story is a collaboration with Chatelaine, which has been publishing award-winning journalism on issues that matter to Canadian women for over 90 years.

On a snowy day last November, Indigenous land defenders head out to hunt on Wet’suwet’en territory in northwest B.C. with hopes of catching a moose to feed their families and Elders. They still haven’t secured any moose meat this season and are starting to stress.

Soon after the small group arrives at their traditional hunting blind, which looks like a tree house, workers from TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink pipeline

project move in on them and threaten to call the RCMP. It’s fight or flight.

The construction of the controversial natural gas pipeline across northern B.C. is opposed by Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs but supported by all 20 elected band councils along the route. It has led to a series of tense confrontations on the territory over the past few years. In February 2020, just over a month after the B.C. Supreme Court granted Coastal GasLink an injunction against land defenders blocking work on the pipeline, heavily armed RCMP raided several camps and arrested 28 people. This sparked the Shut Down Canada movement, which brought Canada’s rail system to a near standstill, just before the COVID-19 pandemic really shut things down. Despite ongoing opposition, the pipeline pushes ahead, even during the pandemic.

Howilhkat (Freda Huson) stands in ceremony while police arrive at the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre on Wet’suwet’en territory to enforce Coastal GasLink’s injunction against land defenders blocking work on the pipeline on Feb. 10, 2020. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Karla Tait, a psychologist and director of clinical services for the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre, is arrested on Feb. 10, 2020. RCMP eventually arrest 28 land defenders over five days of raids. “We are a matrilineal culture, so our women are our strength,” Tait previously told The Narwhal.”So it really feels like it’s a deep responsibility for us as women to make sure there’s territory intact, there’s a safer future for our children that are coming and that these lands will remain here and remain a sanctuary for our people.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Police officers stand guard as Coastal GasLink workers take down red dresses that signify Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls near the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre. Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found “work camps, or ‘man camps,’ associated with the resource extraction industry are implicated in higher rates of violence against Indigenous women at the camps and in the neighbouring communities.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The workers are at the hunting blind to clear the trees — and the people — along the pipeline right-of-way.

“I’d like you to leave the area,” an unmasked worker in a bright-yellow jacket and white hard hat says as he approaches a young female land defender.

“Don’t get close to me. There’s a pandemic!” she yells, filming the incident. “Step back away from me!”

“We have the authority to work here,” he continues.

“You don’t have any authority,” the woman interjects.

“I can feel your breath right now. This is a pandemic. Step away from me!”

As the pandemic gripped Canada in spring 2020, provinces and territories announced that only “essential services” that preserve life, health and basic societal functioning were allowed to continue operations. Across the country, the majority of industrial projects got the green light. Since then, there have been repeated calls from health-care professionals, Indigenous leaders and environmental groups to shut many of them down.

Such critics point out that industrial projects bring hundreds — even thousands — of transient workers from across Canada into remote communities, where they typically live in shared accommodations. Meanwhile, Indigenous workers on such projects often go home to their families.

This has all put Indigenous people at higher risk of catching COVID-19 when they’re already more vulnerable to the disease due to long-standing health inequities, including disproportionate exposure to polluting industries and lack of access to health care. And, as predicted, there have been several outbreaks at industrial work sites across Canada, including at two Coastal GasLink camps. Some have spread to the Indigenous communities nearby.

“It’s like purposefully infecting our people with this disease that’s killing off our most sacred knowledge holders and language keepers,” says Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham). A supporting chief in the Cas Yikh House of the Gidimt’en Clan, one of five Wet’suwet’en clans, she has just attended the memorial of an Elder, one of several to have died from COVID. “We’re never going to be able to recover from those losses. I’m so angry because it was 100 per cent preventable.”

Critics say allowing industrial projects to press on with full knowledge of how Indigenous people could be affected is exposing and exacerbating environmental racism. That’s what it’s called when governments and corporations disproportionately locate polluting industries and hazardous sites in Indigenous, Black and other racialized communities — particularly those that lack the economic, political or social clout to fight back.

Environmental racism has long exposed people to a wide range of health-harming pollutants that have been linked to serious illnesses, including cancer, lung disease and heart conditions. Those ailments, in turn, make people more vulnerable to COVID-19. Now, as industrial projects continue on during the pandemic, COVID-19 itself can be seen as yet another pollutant being circulated by industry. And experts warn we’ll see more pandemics if we continue to exploit our natural environment.

Sleydo’, her husband and their three kids, aged one, five and 10, live in a cabin the couple built deep in the wilderness on Wet’suwet’en territory. Over the past decade, several land

defenders have reoccupied the land and built traditional infrastructure, a healing centre and camps. The goal is to live a traditional lifestyle and protect the territory from industrial development and the people from environmental racism.

“We are the land and the land is us,” says Sleydo’, who is the spokesperson for the Gidimt’en Checkpoint, one of the camps that was raided by the RCMP. “And one is not well without the other.”

In 2019, Baskut Tuncak, then the United Nations special rapporteur on toxics and human rights, visited Canada and documented an epidemic of environmental racism. “There exists a pattern in Canada whereby marginalized groups, and Indigenous peoples in particular, find themselves on the wrong side of a toxic divide, subject to conditions that would not be acceptable in respect of other groups in Canada,” he wrote in his report.

There are plenty of examples. In Alberta, oilsands development has encroached on two dozen Indigenous communities — home to about 23,000 people — since extraction began in the 1960s. In Ontario, more than 60 oil refineries and chemical plants have surrounded Aamjiwnaang First Nation since the 1940s, creating what’s known as “Chemical Valley,” one of the most polluted places in the country. In Nova Scotia, politicians plunked a dump in the heart of Shelburne’s Black community in the 1940s; it closed in 2016, but people are still worried about its lingering effects. And there have long been concerns that the pollution from these projects is causing serious health issues and killing people: environmental racism also involves failing to meaningfully consult communities about such developments in the first place and then taking a long time to address issues that arise.

Baskut Tuncak’s 2019 visit to Canada as United Nations special rapporteur on toxics and human rights included a stop in Ontario’s “Chemical Valley,” which borders the Aamjiwnaang First Nation. “The environmental injustice is an ongoing tragedy,” he wrote in an end-of-visit statement. Photo: Garth Lenz

Residents of Sarnia, Ont., have long raised concerns about the cumulative effects of the pollution from “Chemical Valley” on their health. Many people have lost loved ones to cancer, and research shows rates in the region are higher than in other parts of Canada. A local cemetery is shown here. Photo: Garth Lenz

Ada Lockridge, a member of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, stands in a traditional burial ground with a Suncor refinery in the background. She has been fighting for her community’s right to a healthy environment for decades. Photo: Garth Lenz

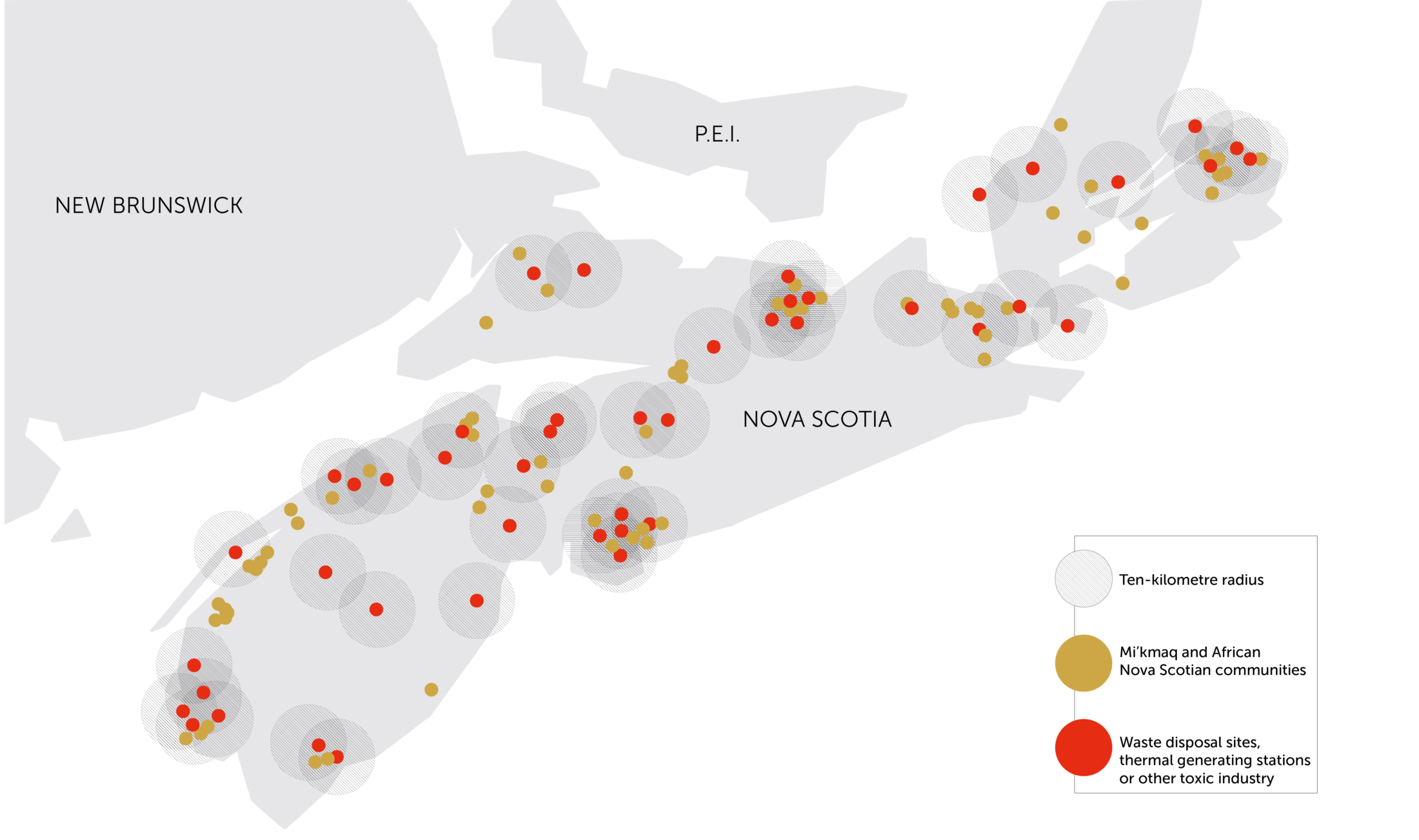

In 2012, Ingrid Waldron founded the Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities and Community Health (ENRICH) Project to study environmental racism in Nova Scotia. In 2016, ENRICH created an interactive map of the province’s waste disposal sites, toxic industries and thermal generating stations juxtaposed with Mi’kmaq and African Nova Scotian communities. A clear pattern emerged.

A sociologist and associate professor in the faculty of health at Dalhousie University, Waldron says the map shows “the audacity of government to select certain communities to put something that’s not desirable.”

When the ENRICH Project plotted polluting industries and racialized communities on a map of Nova Scotia, a concerning correlation emerged. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Waldron eventually turned her research into a book, There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities, and then a 2019 Netflix documentary co-directed by Elliot Page.

She says environmental racism is rooted in colonial policies that allowed settlers to extract resources from Indigenous lands without permission — policies that continue to inform government decision-making today.

“Environmental racism is a visible manifestation of environmental policy,” says Waldron. “And environmental policies are created by members of the elite, mostly white people, who hold perceptions about who matters and who does not matter.”

Ingrid Waldron, founder of the ENRICH Project, has been studying environmental racism for nearly a decade. She says it’s an important topic to tackle because it has profound effects on racialized people’s health and well-being. Photo: Darren Calabrese / The Narwhal

Sleydo’ agrees. “Environmental racism is based on this idea that we aren’t human enough to deserve a clean environment. Nobody cares if we get sick and die because we’re just Indigenous people. And industry and government are banking on that.”

The 22,000-square-kilometre Wet’suwet’en territory — which is about four times the size of Prince Edward Island — has already been irreparably damaged by industrial projects. In the 1950s, Alcan dammed a river, leading some caribou to drown as they attempted to cross new bodies of water en route to their usual habitats. In the 1980s, toxic tailings from a silver mine seeped into a lake, decimating salmon populations. And throughout the decades, logging companies have scarred the landscape with clearcuts, destroying moose habitat.

“Elders that have come out to the territory don’t even recognize it anymore,” Sleydo’ says.

Now, construction on the 670-kilometre Coastal GasLink pipeline — which is set to slice through old-growth forests, wetlands, rivers and habitat for endangered caribou — threatens Wet’suwet’en people’s food and water sources, their cultural sites and their ways of life.

Coastal GasLink workers have cleared hundreds of trees along the 670-kilometre pipeline route. On Jan. 4, 2020, Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs representing all five clans issued the company an eviction notice, saying it has “bulldozed through our territories, destroyed our archaeological sites and occupied our land with industrial man camps.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Mike Ridsdale, an environmental assessment coordinator for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, examines a culturally modified tree. Several such trees — which show signs of being used for traditional practices such as making clothing or shelter — have been cut down to make way for the pipeline, despite opposition from Hereditary Chiefs and land defenders. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

In 2019, Wet’suwet’en Elders sent a small group of people to examine an area Coastal GasLink had cleared to construct a work camp. The group discovered several lithic stone tools, two of which are shown here. The Elders thought the discovery would deter construction at the site. It didn’t. Today, the area is home to Coastal GasLink’s 9A Lodge. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Sleydo’ says work on Coastal GasLink is not only racist, it’s also illegal: the Wet’suwet’en never ceded their territory to the federal government. The Hereditary Chiefs have jurisdiction over it, according to Wet’suwet’en law. This is backed by the 1997 Supreme Court of Canada Delgamuukw decision, which stated that provinces can’t extinguish Aboriginal Title (which includes rights to natural resources) and that oral history is legitimate evidence of land claims. According to the Hereditary Chiefs, the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline is a violation of their law and, as such, they’ve issued the company an eviction notice.

It’s also a violation of international human rights law, according to watchdogs. In December 2019, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination called on Canada to halt work on the Coastal GasLink pipeline — as well as two other industrial projects in B.C. — until it receives free, prior and informed consent from Indigenous Peoples. It also urged the country to stop removing Wet’suwet’en people from their lands and start removing police and security forces.

Yet while the pandemic offered the perfect opportunity to hit pause on these projects, they continue on with the blessing of the government and, in the case of Coastal GasLink, the help of the RCMP.

At a media conference soon after B.C.’s essential services list was released, Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry explained why industrial projects made the cut. “I think it’s important to recognize you can’t just abandon a large mine or industrial site. That’s not safe; it’s not safe for the community or for the environment, as well,” she said.

Three weeks after the province released initial COVID-19 safety guidelines for industrial work camps, Henry issued a public health order requiring specific safety protocols. It didn’t limit the number of workers, although many projects, including Coastal GasLink, voluntarily reduced their workforces — at least for a while.

The number of workers at Coastal GasLink camps went from about 1,130 at the end of February 2020 to 130 at the end of March. However, the number of workers on industrial projects fluctuates seasonally, and Coastal GasLink described the reduction as a “scheduled ramp-down.” By November, in the midst of the second wave of the pandemic, there were more than 4,000 people working on the pipeline.

While governments said it was safe for work to continue on industrial projects, some said, paradoxically, that environmental monitoring was unsafe. The Alberta Energy Regulator gave the entire oil and gas industry a months-long break from a long list of environmental activities, such as most ground and surface water monitoring and almost all wildlife monitoring. At a media conference, Alberta NDP leader Rachel Notley called the move “a cynical and exploitative use of this pandemic” and also tweeted, “So, people can get haircuts in most of the province right now, but we can’t test the water supply for cancer-causing agents?”

Critics questioned why industrial projects that don’t provide any essential services to Canadians (and never will) got the go-ahead. The Coastal GasLink pipeline, for instance, is being built to transport natural gas across the province to be exported overseas. LNG Canada, the export facility, is also under construction.

To many, the risks seemed unnecessary. Just over a week after B.C. declared a state of emergency, David Bowering, former chief medical health officer of northern B.C.’s health authority, released an open letter to Henry calling work camps “landlocked cruise ships” and “COVID-19 incubators” and urging her to shut them down.

“Landlocked cruise ships.” Industrial work camps across the country have been housing hundreds, even thousands, of workers during the pandemic. LNG Canada’s 1.2 million-square-foot Cedar Valley Lodge, shown here, can accommodate 4,500 workers. Photo: LNG Canada

In November 2020, there were at least two COVID-19 cases at Coastal GasLink’s 9A Lodge, shown here, according to Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham). The company has reported a total of 85 cases across work sites as of March 16, 2021. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Other letters followed: front-line health-care workers, Indigenous leaders and environmental groups all asked Henry to put people before profit. One of those letters was from Sleydo’ and her fellow female chiefs. “The economy cannot come before Indigenous lives,” they wrote.

Despite the pleas, Henry didn’t take any action until the end of December, after a series of cases, clusters and outbreaks at work sites in northern B.C., some of which spread to Indigenous communities. She then issued a public health order outlining a gradual return of the workforce to the sites following the Christmas holidays. Between November and January, there were outbreaks totalling 56 cases at Coastal GasLink sites and 72 cases at LNG Canada sites. (Henry was not available for an interview.)

Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham) and other land defenders have had several ceremonies on their territory interrupted by unmasked Coastal GasLink workers and RCMP officers during the pandemic. “They have no moral compass, no understanding of us as a nation and our practices, and no respect,” she says. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Sleydo’ says Coastal GasLink workers and RCMP officers aren’t always following basic safety protocols, such as wearing masks and maintaining a distance of two metres from others. This can be seen in several incidents captured on camera and posted to social media, in which workers and officers approach land defenders who are hunting, holding ceremonies and patrolling the territory.

“They’re taking advantage of a global pandemic to further destroy our lands and put our people at risk, which I think is really disgusting,” Sleydo’ says.

Coastal GasLink did not reply to several interview requests. In an email, an RCMP spokesperson said officers should be wearing masks when interacting with the public.

After Yellowknife emergency room doctor Courtney Howard had her first daughter in 2011, she spent a lot of time breastfeeding and staring out her window at Great Slave Lake, which is downstream from the oilsands. She decided to do some research into how they affected community health. She figured she’d find a ton of peer-reviewed studies, but she turned up zero.

“The lack of research into the local health impacts of the oilsands is astonishing,” says Howard, who is past-president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment. “It is so far beyond what any of us should consider acceptable as members of this country.”

Unfortunately, Howard says, that’s the norm for research into what effects resource extraction industries might have on the health of those who live nearby. She can think of a few reasons for the data gap. Communities that are “out of sight, out of mind” may not attract the attention of researchers. Remote communities often lack continuity of care, so health-care providers may not notice things like a cluster of a rare type of cancer. And they may face environmental racism. “When the communities raise the alarm, it is not always acted upon the way that it should be,” Howard says.

A decade ago, Yellowknife emergency room doctor Courtney Howard couldn’t find any peer-reviewed studies on the local health effects of the oilsands. Since then, she says, there have been a few studies, but none of adequate scale or scope, leaving a potentially deadly data gap. Photo: Pat Kane / The Narwhal

What is known about the local health effects of heavy industry isn’t good. For instance, a 2019 study in the journal Cancer found the rate of acute myeloid leukemia in one area of Sarnia, Ont., near Chemical Valley, is three times higher than the national average and suggested pollution from local oil refineries and chemical plants may be to blame.

And while there’s a lack of studies on communities affected by environmental racism, there’s ample research on the impacts of the pollutants they’re exposed to. Waldron recently combed through decades of research to pull together a report on the health effects of toxins found in waste sites, thermal generating stations, and pulp and paper mills. She found that the toxins — heavy metals, volatile organic compounds, fine particulate matter and mobile gases — are associated with a long list of health issues, including cancer, birth defects and damage to most of the major organs.

Air pollution has also been well studied and has been linked to heart, breathing and lung conditions. It contributes to an estimated 14,600 premature deaths in Canada every year. Emerging research from around the world also suggests that chronic exposure to air pollution makes people more likely to catch COVID and die from the disease.

Physicians may be scared to speak out when they notice concerning health trends in areas beset by industry. In 2007, after Dr. John O’Connor raised concerns that high rate of cancer in Fort Chipewyan, Alta., could be linked to the oilsands, Health Canada doctors accused him of causing “undue alarm.” Two years later, he was cleared of any wrongdoing and in March was awarded the inaugural Peter Bryce Prize for whistleblowers. Photo: Kris Krüg

In March, during an online ceremony for the Peter Bryce Prize, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam said more people in his community have died of cancer than of COVID-19 during the pandemic. The local cemetery is shown here. “People are being diagnosed still with cancer, but nobody’s sayin’ nothin’ about it, nobody’s doin’ nothin’ about it,” he said. “When it comes to development, it seems like government and industry work hand in hand.” Photo: Kris Krüg

Environmental racism can also lead to stress and mental illness, which can, in turn, result in physical harm. Waldron says many chronic diseases that were once thought to be primarily genetic, like diabetes, are largely influenced by structural inequities such as environmental racism. “We know now that racism gets under your skin and actually changes your biology,” she says.

In Canada, COVID-19 data on race is not being systematically collected at the federal level, but some provinces, cities and health authorities have started to crunch the numbers. In the United States, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows Black and Indigenous people are about five times as likely to be hospitalized for the disease as white people. Environmental racism is but one reason for the chasm.

Research shows that racialized people in Canada have worse health outcomes and higher rates of chronic diseases due to a number of social and economic factors, including poverty, food insecurity and unstable housing. They’re also more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as extreme weather and new diseases.

“There’s overlapping systemic discrimination that leads to overlapping health impacts,” Howard says. “It would be difficult to tease out what the exact impact of environmental racism would be—and that’s a frequent excuse we hear from industry.”

Another layer of discrimination is in the health-care system: when Indigenous people do get sick, whether it be with COVID or another illness, they often face racism when trying to get treatment. In September 2020, Atikamekw mom of seven Joyce Echaquan died in a Quebec hospital after she livestreamed staff saying she was “stupid,” “only good for sex” and “better off dead” as she cried out in pain. In B.C., just two months later, an independent investigation found that 84 per cent of Indigenous people have experienced racism in the province’s health-care system.

“Every way you look, it’s like, ‘You don’t matter, we don’t care about your life, we don’t care about your land, you have no rights. You don’t even have the right to live,’ ” Sleydo’ says. “And then, when you do get sick, you’re put into this system that’s racist against you and you’re expected to somehow survive. And people aren’t surviving.”

Scientists are still trying to pin down the origin of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. But they know one thing for sure: it’s zoonotic, meaning it jumped from an animal to a human. It’s just the latest in the rising trend of zoonotic diseases, following the likes of Ebola, SARS and Zika.

Three-quarters of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, and scientists warn that we’ll see more pandemics if we continue to exploit nature. Here are some of the top human drivers of zoonotic diseases, according to the UN Environment Programme.

Climate change can have a huge influence on organisms that cause diseases and the animals that carry and transmit those diseases. It can affect where they live, how long they survive and how much they reproduce. For instance, as temperatures rise, ticks are marching into new parts of Canada and enjoying a longer season.

Climate change is also causing more frequent and more intense extreme-weather events, which scientists have linked to infectious disease outbreaks. Heavy rainfall, for example, creates more breeding grounds for mosquitoes and more crops for rodents, allowing them to grow their armies.

As the world warms and Arctic permafrost melts, humans and animals that have been buried for centuries are becoming exposed. Perhaps the most terrifying disease prospect is that long-dormant “zombie” viruses and bacteria may rise from the dead and infect us again.

Resource extraction in remote areas often destroys wildlife habitat. When people are working in these areas, they’re more likely to have interactions with the animals that live there and be exposed to zoonotic diseases.

The growing demand for animal protein has led to an increase in factory farming. Companies often breed genetically similar animals that yield more meat and keep them in close quarters. Both factors make them more vulnerable to disease. Swine flu, for instance, first spread among pigs housed in factory farms and then jumped to humans.

In February 2020, in the midst of the Shut Down Canada movement, Teck Resources withdrew its regulatory application for its controversial Frontier oilsands project in northern Alberta. When explaining why in a letter to Environment and Climate Change Canada, Teck president and CEO Don Lindsay said Canada needs to reconcile resource development, climate change and Indigenous Rights.

While Lindsay said the decision had nothing to do with a “vocal minority” opposed to the project, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney and then federal Conservative leader Andrew Scheer were quick to blame opponents, who were happy to take credit. The group Indigenous Climate Action, which campaigned against the project, called it “a win for Indigenous Rights, sovereignty and the climate,” while adding that the fight against environmental racism is far from over.

For years, affected communities, environmental advocates and other groups have been pushing the federal government to update the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, including amending it to legislate the right to a healthy environment. More than 150 countries have already done so, and it’s one of 87 recommendations that came out of an extensive review of the act in 2016 and 2017 (many of which are also echoed in the UN report that called out Canada’s environmental racism). While Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has asked the ministers of health and environment to work on strengthening the act, it could be yet another issue sidelined by the pandemic.

Nova Scotia MP Lenore Zann says her private member’s bill to redress environmental racism is designed to address long-standing systemic inequities in Canada. “My hope is that we can put some teeth into the rights of humans to clean air and clean water and being safe on their land,” she says. Photo: The Canadian Press / Andrew Vaughan

Mi’kmaw artist Melissa Labrador runs her hand through the grass where she harvests medicinal plants in the Wildcat community of Acadia First Nation near Kejimkujik National Park in Nova Scotia. Photo: Darren Calabrese / The Narwhal

Meanwhile, Nova Scotia Liberal MP Lenore Zann has introduced a private member’s bill calling for a national strategy to redress environmental racism. The bill, which Waldron collaborated on, suggests collecting data on the problem as a prelude to amending laws, engaging communities in policy development and compensating individuals and communities for harms they’ve suffered.

“Grassroots warriors across the country have been fighting this fight for so long, but they were ignored,” Zann says. “It’s time that we listen and that we act.”

Waldron first approached Zann for political support in 2014, when Zann was a provincial MLA. The politician suggested developing a private member’s bill to redress environmental racism. She cautioned Waldron that private member’s bills rarely pass but said it would generate a ton of political debate, media attention and public awareness, which is exactly what happened.

“It got people talking about the issue, which was our main goal,” Zann says. “Environmental racism is like a wound. You have to bring it out into the light of day, dig out whatever is in there and clean it in order for it to heal.”

When Zann moved to federal politics, her first order of business was working on a national bill. At press time, the continuation of the bill’s second reading was scheduled for late March. Zann says she’s “cautiously optimistic” the bill will move to the next stage.

Recent action to address environmental racism in the U.S. may give Zann’s bill the boost it needs. In January, President Joe Biden signed an executive order directing federal agencies to develop programs and policies “to address the disproportionate health, environmental, economic and climate impacts on disadvantaged communities.”

A month after the incident at the hunting blind, on Sleydo’’s son’s 10th birthday, her husband burst into the cabin and told his family to get ready: he’d caught a moose. They loaded into the car and radioed people at the Gidimt’en Checkpoint, giving them the coordinates and asking them to meet there without explaining why.

After the family arrived, two carloads from camp showed up frantically, expecting an incident with Coastal GasLink workers or the RCMP. Then they saw the moose. After a collective moment of relief and excitement, they paid their respects to the animal through ceremony, with the kids putting medicines in its eyes and ears, and then harvested it.

Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham) says special moments on the land with her kids — including one-year-old Winïh, shown here — keep her going. “I want a safe, healthy territory — yintah — for them and for their kids,” she says. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Back at the cabin, the family had an outdoor fire, cooked up the organs and played games. Sleydo’ felt a deep sense of satisfaction, security and reciprocity.

“I always tell the kids, ‘If you take care of the land, the animals know that and they give their lives up for you,’ ” she says. “I really believe that when we eat animals from the territory, it gives us the spiritual and physical strength to keep fighting.”

And the fight to protect Wet’suwet’en lives — during the pandemic and beyond — is far from over.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Notes made by regulator officers during thousands of inspections that were marked in compliance with...

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...